You litter, I…?

Social Influence on Littering

Whether someone carelessly drops a scrunched-up ATM receipt on the floor, leaves their plastic bottle on a bench or casually flicks a cigarette butt out of the window instead of using designated bins:

Littering is not just a question of aesthetics, – clearly it does uglify places – . It also contributes significantly to the global problem of environmental pollution.

Plastic litter that casually gets into waterways eventually floats on ocean surfaces, ends up in animal guts or takes decades to disintegrate under water.

Why do we see huge amounts of littered waste in the world? What drives littering behaviour?

It’s safe to say that littering is not really “cool” (apart from stubbing out cigarettes on the pavement, it seems). It’s not a socially desirable behaviour. On the contrary, it’s generally considered “bad” and unnecessary to dispose of one’s trash on the beach or in the woods. Still, why do people litter?

Famous social psychologists Cialdini, Reno and Kallgren precisely looked at this question. Their seminal work investigated the influence other people have on our behaviour.

Social influence, they postulated, works through 2 distinct types of social norms:

DESCRIPTIVE NORMS or norms about what is

INJUNCTIVE NORMS or norms about what ought to be

|

This theoretical refinement is key to understanding social norms.

Most of the time, in daily life, we are not consciously aware of their influence, because both norms are well-aligned and internalised. (Or one might argue, that we are so well aware of them that we don’t need a reminder).

For instance, most people routinely cross the street when the traffic light turns green (descriptive norm); and that’s also what is expected (injunctive norm).

What about littering?

Despite the widely held (injunctive) norm in society that littering is ‘bad’, what about the typical behaviour of people? Here it gets tricky.

Suppose, you go somewhere and litter is all over the place. Obviously, “littering” appears to be the norm. A clean, pristine environment, on the other hand, tells you the opposite. “If virtually no one litters [here]”, then “anti-littering” is the norm.

First thing to note here: norms are not always aligned. As in the case of littering, they may point in opposite directions. If so, which norm will be decisive in influencing your behaviour?

And, what about other factors and considerations, like environmental awareness, convenience or absence of trash cans?

Cialdini et al.’s hypothesis: normative considerations are extremely powerful – but, not always. Only when you FOCUS on the relevant norm, as you’re about to take action.

And so, they reasoned, if you get people to focus either on the littering norm or on the anti-littering norm, you should get different results: precisely, more or less littering.

Testing the hypothesis: The littering study

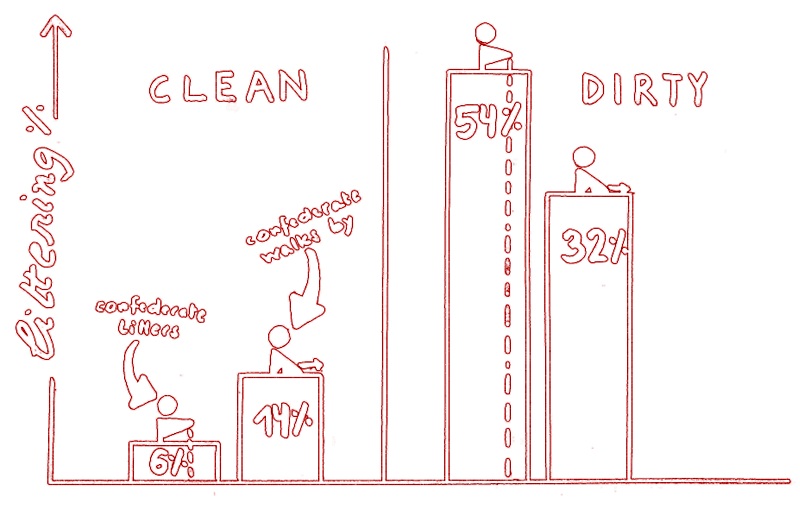

In their first study, participants have to return individually to a parking garage. The garage is either clean or dirty (heavily littered).

First thing to note here: The state of the garage is supposed to reflect the typical behaviour of garage users (i.e., the descriptive norm). A clean garage conveys that “no one litters here” (the anti-littering norm), while a dirty garage conveys that “everybody litters here” (the littering norm).

In the garage, participants witness a confederate reading a large handbill and then either dropping it on the garage floor (littering) or just walking by (not littering).

The confederate’s role is to focus the participant’s attention on the state of the environment (clean or littered), thereby making the relevant norm prominent.

That’s important because without such focusing procedure, it could well be that participants do not even take note of it.

Participants then get back to their car, where they find an identical handbill tucked under the windshield wiper so as to partially obscure vision.

How will they get rid of the handbill? By dropping it (littering) or by keeping it in the car (as there are no trash receptacles nearby)?

| Condition | garage | confederate |

|---|---|---|

| I | CLEAN | litters |

| II | CLEAN | walks by |

| III | DIRTY | litters |

| IV | DIRTY | walks by |

Results

1. People littered more often in a dirty garage than in a clean one. – this might already hint at the fact that people do follow the typical behaviour of others.

2. People littered even more frequently (54%) in a dirty environment when they saw the confederate litter the handbill vs. when the confederate just walked by.

Focusing attention on the littering norm changes individual behaviour in the direction of this very norm – producing even more littering. This happens even though everyone knows that you’re not supposed to litter.

Can we rule out the alternative explanation, that participants merely imitated the confederate’s behaviour?

A surprising result offers an answer:

3. Of all conditions, least littering (6%) occurred when people saw the confederate litter into a clean environment: When the typical behaviour of garage users is “anti-littering”, except for ONE aberrant litterer (the confederate).

The researchers replicated this result with 2 other studies.

Least littering occurred when…

or, when…

|

What these results have in common

They focus participants’ attention on a violation of the descriptive norm (“no one litters here EXCEPT 1”); but also, on a violation of the society-wide injunctive norm (“you’re not supposed to litter”). Thus, seeing someone so evidently violate the society-wide norm enhances individual compliance with it.

Final conclusion: how to end littering?

If our aim is to reduce littering in society, we should not draw attention to the descriptive norm, unless a spot is clean or virtually clean. Otherwise, it produces the opposite effect: more littering.

Instead, the most effective use of social norms is to focus people’s attention directly on the injunctive norm, because it gives clear evidence on what is approved or disapproved by society. That way, you can arrive at pro-social and pro-environmental behaviours – even in awfully littered places.

Written and published September 2021

by Jessica

References

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of personality and social psychology, 58(6), 1015.

Kallgren, C. A., Reno, R. R., & Cialdini, R. B. (2000). A focus theory of normative conduct: When norms do and do not affect behavior. Personality and social psychology bulletin, 26(8), 1002-1012.