Happiness in Perspective

Why care about happiness?

The growth mindset

Whenever there is talk of national or individual wellbeing in the media, more often than not economic growth is mentioned.

Not least because economic growth is expected to bring about a virtuous circle of positive effects: from a raise in living standards, income and tax revenues to a stimulus in employment and investments – (the latter is the so-called accelerator effet).

That is why, compared to all other indicators of wellbeing (e.g. the Human Development Index (HDI) or the OECD Better Life Index), GDP and GNP (Gross Domestic/National Product) attract by far greatest attention.

Yet, people grow more and more disillusioned with governments’ overemphasis on economic growth.

The downsides are apparent

► For one, producing ever more stuff is environmentally destructive, even more so as it results in tons of waste and only a small fraction is currently recycled or upcycled in the circular economy.

► The returns generated by economic growth are not at all evenly distributed; the gap between rich and poor is steadily growing. Sadly, emerging countries all too often tell a cautionary tale about how growth does not necessarily bring about sustainable, social and just development.

The bottom line here is the following: economic growth is neither a warrantor for everything in the world that’s deemed good nor the answer to all our problems. And: it doesn’t necessarily make us any happier.

“Surveys in Britain and the U.S. show that people are no happier now than in the 1950s – despite massive economic growth.”

actionforhappiness.org (‘20 Happiness facts‘)

Why care about happiness?

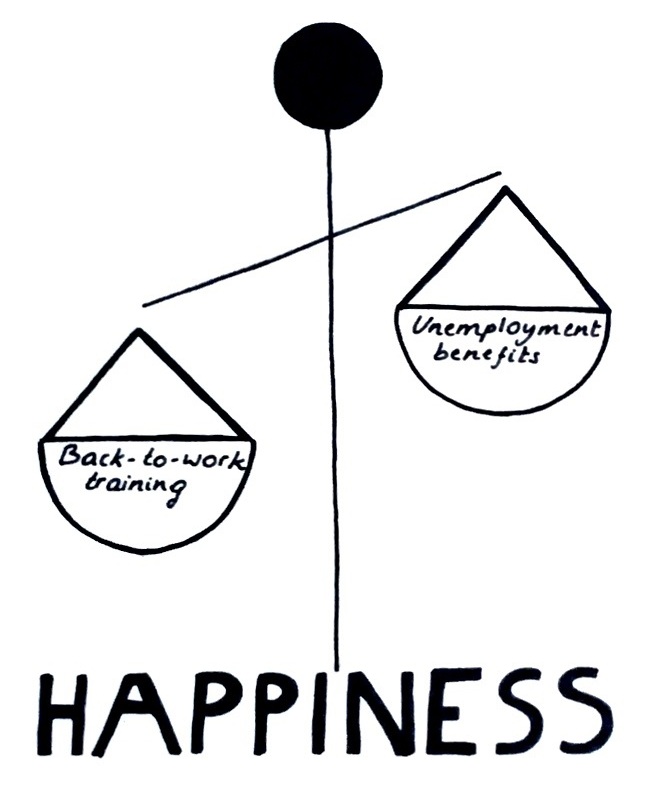

If you think about it, a key role of government and public policy is to allocate and re-allocate resources efficiently and fairly in society. From this vantage point, wellbeing (and happiness) is not just a private matter but something that is clearly impacted by policy decisions.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that overall life satisfaction correlates with things like health, employment, income, family relationships and social networks – at least three out of which are clearly in the scope of public policy.

Innate or acquired?

According to the Action for Happiness project around 50% of variations in happiness between individuals can be explained by ‘genetic factors and upbringing’, 40% by ‘activities and relationships‘ and 10% by ‘income and environment‘.

The science of Happiness

Over the past 15 years interest in the study of happiness, positivity and mindfulness has grown in academia (and in popular science). Positive psychology has emerged as a new movement that seeks to shift psychology’s long-standing focus on mental illness (“–“) towards mental health (“+“).

Happiness has truly turned into an interdisciplinary science: It is not just relevant to psychologists (e.g. Daniel Kahneman). Sociologists (e.g. Ruut Veenhoven) and economists (e.g. Richard Layard and Paul Dolan) alike care about happiness.

Happiness as a benchmark

Now here’s my claim: When it comes to evaluating and judging whether a particular public policy – on taxation/redistribution, employment or health … – is well chosen, people’s happiness (and wellbeing) should be the important criterion and benchmark.

“We need a revolution in academia, with every social science attempting to understand the causes of happiness. We also need a revolution in government. Happiness should become the goal of policy, and the progress of national happiness should be measured and analysed as closely as the growth of GNP.”

Richard Layard (2005: 145, 147)

The long-held belief that happiness could not be measured and is therefore not (statistically) relevant to policy making has clearly been disproven: In the past decade different measures of happiness have been developed and put into practice. And: they gain every day in significance for public policy.

Coming up next

I offer you 3 possible ways of defining and measuring happiness for policy purpose. I’ll talk you through relevant pros and cons.

Stay tuned ! 🐝

Written and published July 2019

by Jessica

List of references I used in this article:

actionforhappiness.org

Dolan, P., Peasgood, T. and White, M.P. (2008) ‘Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective wellbeing’, Journal of Economic Psychology, 29 (1): 94–122.

hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-hdi

Kahneman, D., Diener, E. and Schwarz, N. (eds) (1999) Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology, New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Layard, R. (2005) Happiness: Lessons from a new science, London: Allen Lane.

Odermatt, Reto and Stutzer, Alois. (2017) Subjective Well-Being and Public Policy. IZA Discussion Paper No. 11102.

oecdbetterlifeindex.org

Seligman, M. (2002) Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfilment, New York, NY: Free Press.

Seligman, M. and Peterson, C. (2003) ‘Positive clinical psychology’, in L.G. Aspinwall and U.M. Staudinger (eds) A psychology of human strengths, Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 305–317.

Smith, C. (2010) Measurement of subjective well-being: Proposed prototype survey modules, Paris: OECD Advisory Group on Guidelines on the Measurement of Subjective Well-Being.

Tomlinson, Michael W. (2013). Is everybody happy? The politics and measurement of national wellbeing. Policy & Politics, 41(2), 139-157.

Veenhoven, R. (2008) ‘Sociological theories of subjective well-being’, in M. Eid and R. Larsen (eds) The science of subjective well-being: A tribute to Ed Diener, New York, NY: Guilford Press, 44–61.